A home of her own

She put her name on a list for public housing and waited. For eight years, she had no fixed address.

She put her name on a list for public housing and waited. For eight years, she had no fixed address.

Last Christmas was a special one for Jennifer Pudloo. The 25-year old single mother admits that nothing spectacular happened and that her budget was tight. But it was special because, for the first time in eight years, Jennifer spent Christmas in a home she could call her own.

Jennifer grew up in the Nunavut capital of Iqaluit. After graduating high school, she found work with the territorial government and was able to afford a bachelor apartment. But after a year, she lost the job, the income and the apartment. She put her name on a list for public housing and waited. For eight years, she had no fixed address.

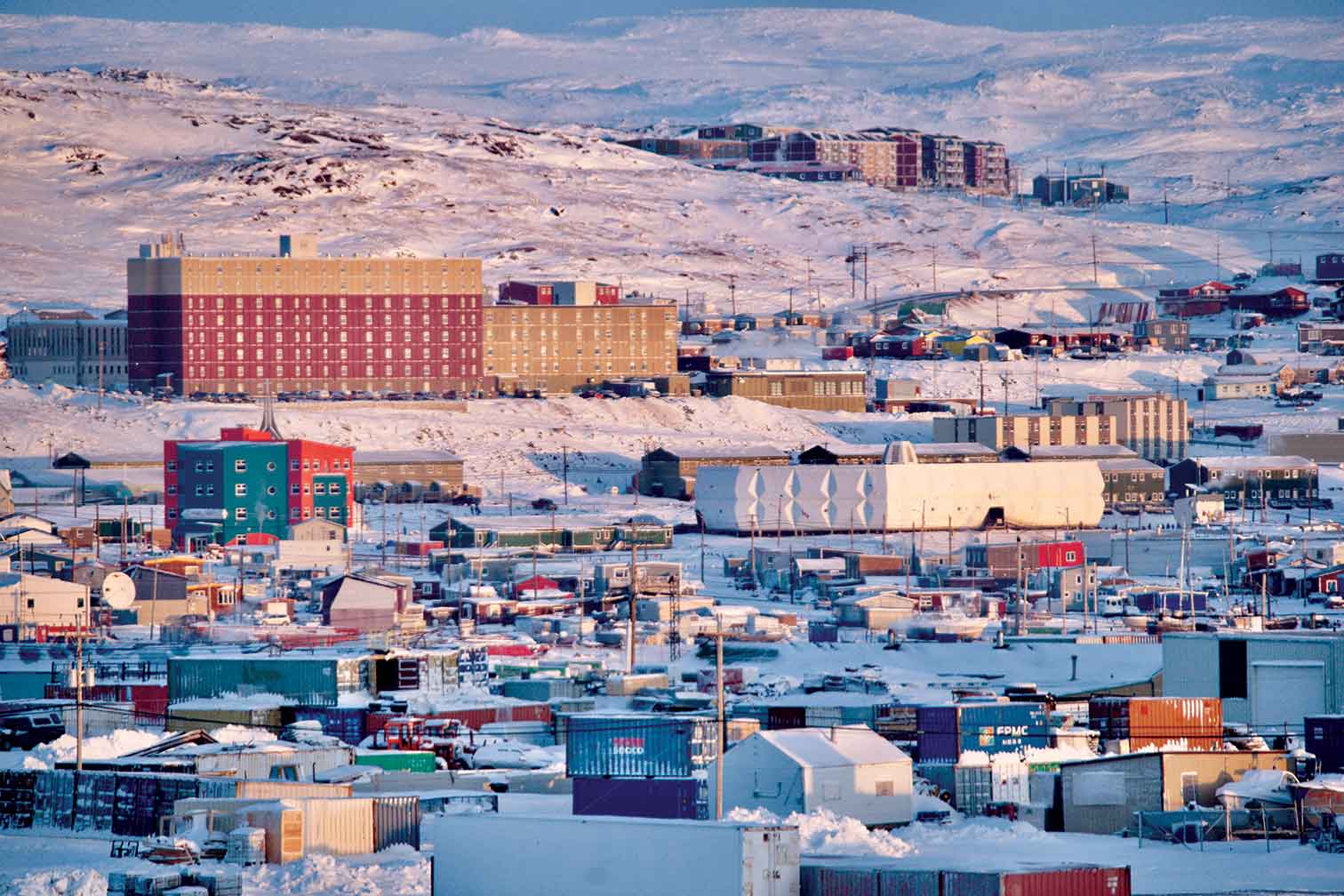

While people in Canada hear a lot about the housing affordability crisis in cities like Vancouver and Toronto, the situation in Iqaluit — where food costs three times the national average and unemployment hovers around 10% — is dire.

With the average market rent of a two-bedroom apartment at $2,600, two thirds of the city’s 7,700 inhabitants rely on housing subsidized by their employer or the government. But housing is sorely lacking. According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 193 new public housing units are needed to meet Iqaluit’s current demand.

With winter lows regularly dropping below minus 30°C, shelter takes on urgent meaning. Like many in Iqaluit, Jennifer bunked in with family members. Over the years, she slept on couches, pull-out beds and mattresses, while working odd jobs at the local hotels or at the soup kitchen. Jennifer and her boyfriend were living with her uncle — he in his single bedroom, two other adults in the storage room, Jennifer and her boyfriend in the living room — when she got pregnant.

As soon as her son Hunter was born, Jennifer realized that her uncle’s “party house” wasn’t going to work anymore. She and Hunter moved into a women’s shelter. Half a year later, she got a call from the public housing office. She moved into her two-bedroom apartment last December.

She can’t imagine living anywhere but Iqaluit.

“It was very, very empty at first,” she says, but now that she’s collected some furniture and her own things, it feels more complete. But not entirely.

“Now that I have a home, I hope I can get my son back,” she says, referring for the first time to an older son, Miles, now eight. Homeless when he was born, she says she “didn’t want to put that emotional burden on him,” so gave him to his father, who then moved to the South. She hasn’t seen Miles in four years.

In 2017, Canada’s Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report on the housing challenges faced by the country’s northernmost communities. Among the committee’s findings: that over half the Inuit in Nunavik, or northern Quebec, live in overcrowded housing; that rates of tuberculosis, caused largely by poor housing, are 250 times higher among the Inuit than Canada’s non-Indigenous population; that housing shortages correlate with “serious public health repercussions” including respiratory and mental illness. The report’s title – “We Can Do Better” – feels like an understatement.

Still, Jennifer’s not complaining. She’s visited a few cities in the South — Toronto, Montreal, Quebec — and found them “amazing” but also overwhelming. She can’t imagine living anywhere but Iqaluit.

In her new apartment, Jennifer enjoys looking out the window at Frobisher Bay, playing peek-a-boo with Hunter in the downstairs playroom or watching television upstairs. She’s reassured by the security camera outside and the dead bolt on the door. And now, she’s setting up a second bed in Hunter’s bedroom in the hopes that one day, his half-brother will come home to them.

In 2018, the Commission submitted its formal recommendations on the federal government’s National Housing Strategy. Our various recommendations were part of an overarching recommendation to apply a human rights approach to the National Housing Strategy. For example, as part of a human rights approach, we recommended that the federal government ensure that the language and concept of human rights in the context of housing is clearly recognized and integrated throughout the entire Strategy. We also recommended that a diverse group of people with lived-experience with either poverty, inadequate housing or homelessness represent at least half of the National Housing Council.