Erasing hate

“I had no idea that by posting pictures and videos of me removing hate, I would inspire others to do the same.”

“I had no idea that by posting pictures and videos of me removing hate, I would inspire others to do the same.”

Corey Fleischer can vividly recall the moment he found the thing he didn’t even know he was looking for. It was a summer’s day in 2009. Corey, 28 years old at the time, was driving his power-washing business truck through downtown Montreal, when he passed a huge swastika spray-painted on a cinderblock at the side of the road.

He carried on to his job in the suburbs, but as he watched his eight-man crew scour a driveway clean, an arresting thought hit him. He sent his workers home, promised the customer to return the next day and drove back to that swastika. After twenty seconds of power-washing, the swastika was gone and with it, a feeling of aimlessness that had been weighing on Corey for years.

“It was an epiphany,” he says today. Watching the “colours bleed off that concrete slab” gave Corey a surge of satisfaction unlike anything he had ever felt before. He wanted to feel that way again. And again.

Since then, Corey has made it his mission to rid the public realm of signs of hate. For years, he kept his work to himself, fearing people would think he was “crazy.” Instead of playing softball or hockey, Corey would come home from work, pick up his dog and jump back in the truck to go looking. It was a scavenger hunt of sorts and every hateful piece of graffiti he sanded, chiseled or blasted into oblivion gave him an addictive high.

After five years working alone, in which he estimates he removed 50 pieces of hate from the greater Montreal area, Corey decided it was time to let others know what he was up to. He sat for hours at his computer, deliberating over whether he should really post some photos of his recent removals to Facebook. He feared judgement. Then he hit enter.

The next day, his social media feeds were on fire. There were countless media requests, but also messages from people from all over the world, alerting him to hateful graffiti in their towns or cities.

“That’s when the circle really started turning,” says Corey. “I had no idea that by posting pictures and videos of me removing hate, I would inspire others to do the same.”

People began posting photos of themselves removing swastikas, curses and insults from cityscapes across the world. Or they would post a photo of something and ask for Corey’s advice on how to remove it. He says that some combination of sandpaper, nail polish remover and a little freshly-mixed cement will usually do the trick. But if it’s more involved than that, he will contact a local power-washer and ask them to do it. And he doesn’t mind paying out of pocket.

In 2018, Corey’s Facebook page got more than 100 million views. He points out that social media, often associated with negative behaviours like bullying, “is what you make of it.” Certainly, the movement that spun out of Corey’s simple gesture would be unthinkable without it.

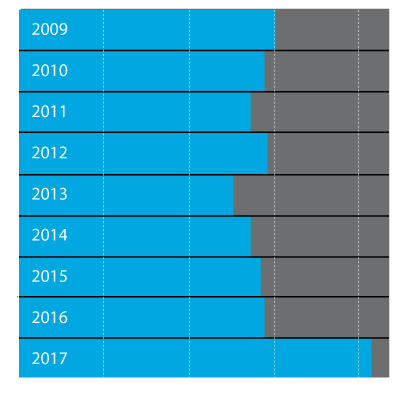

This kind of collective action is heartening. It’s also very much needed. Corey’s movement, which he calls Erasing Hate, has got its work cut out for it. According to Statistics Canada, police-reported hate crimes have been steadily on the rise since 2014, with an alarming 47% increase from 2016 to 2017. The sharpest rises were in Ontario and Quebec, with non-violent hate crimes such as vandalism and graffiti accounting for the bulk of the increase.

Number of police-reported hate crimes

Some may consider these to be lesser misdemeanors — but Barbara Perry, hate crime expert and professor of criminology at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, vehemently disagrees. She calls the visibility and blatancy of graffiti “devastating” to the targeted community, while contributing to a “normalization of hate.”

There’s much speculation about what is behind this ugly upswell, but Corey worries less about root causes than about meeting its manifestation head on: eliminating signs of hate and encouraging others to do the same.

Corey acknowledges that being six foot two and 250 pounds might make his role easier. But ultimately, he feels the people behind these hateful acts are cowards, operating by cover of night and never owning up to what they do. The public erasure of their work is a far stronger statement than the work itself.

The widespread impact of Erasing Hate is inspiring. “A lot of people think that social change requires millions of dollars and complex algorithms,” he says. “All this required was a power washer and some water.”

And courage and determination. But Corey doesn’t play the hero. “I didn’t start with any grand plan,” he says. “To be honest, I started doing this just for myself, because it made me feel good.”

Throughout 2018, the Commission spoke out about the rising issue of hate and intolerance in Canada. At the close of 2018, in an appearance before the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights, the Chief Commissioner encouraged the committee to launch a comprehensive study on hate.